Recording, conserving and promoting the landscape and rocks of the Sheffield region

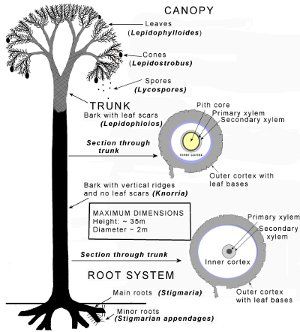

Morphology of arborescent lycopods

Fig. 1 The main features of Lepidodendron

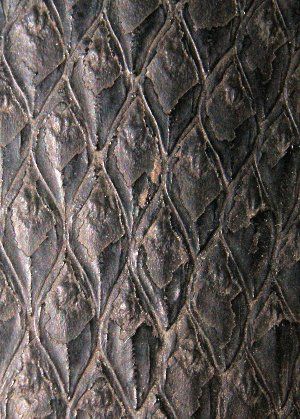

Fig. 2: Lepidodendron sternbegii scaly pattern of leaf scars

Specimen: MuseumsSheffield, Photo: Rick Ramsdale

Fig. 3: Lepidodendron lanceolatum leaf and smaller leaves on terminal branches

Specimen: MuseumsSheffield, Photo: Rick Ramsdale

The term Lepidodendron

has come to represent more than one species of arborescent (tree-like) lycopod. Here, this description deals with the general features of many of these species, some of which are described in more detail in the

Lycopod Palaeoecology

Palaeoecology section

Most reconstructions of Lepidodendron

are misleading: they show only the final mature stage with a crown of branches, but during its short life (estimated at 10 to 15 years) it grew as an unbranched "pole" with spirals of leaves around its trunk. Unlike modern trees, no secondary phloem (cells which transport food products around the plant) was produced at all in Lepidodendron.

Much of the interior was of soft cellular pith which collapsed after death, and, unlike modern trees, these plants were strengthened by the growth of a strong outer cortex. It was the cortex which provided the support for the tall trunks of these plants, and the interior is often fossilised as a sediment filled space. Branches are common fossils, often found flattened, or partially filled with sediment, and, because they were partly compressed during burial, these are usually oval shaped in cross section.

The scaly surface pattern is made up of the leaf scars left behind on the cortex during leaf-fall. It is this leaf pattern that gives the fossil its common name of "Scale Tree". The leaves grew directly from the trunk (not with a stalk) and they always form a spiral around the stem, indicating that the leaves formed a helix around the main axis.

Leaf fossils (Lepidophylloides)

The leaves on Lepidodendron

grew to different sizes depending on which part of the plant they were found. The largest leaves could reach up to a metre in length whilst only being a few centimetres in width. The leaves had a single central vascular bundle (for water transfer) and two grooves on the lower surface with stomata for gas exchange. The distinctive leaf base pattern on the trunk and branches was covered by cuticle, had stomata and was involved in photosynthesis along with the leaves.

Fig. 4: A vertical section through Lepidostrobus

Specimen: MuseumsSheffield, Photo: Rick Ramsdale

Fig. 5: Spore with trilete suture

Photo:Duncan McLean

Cone fossils (Lepidostrobus)

The reproductive cones on lycopods are different to those on pine trees, in both their structure and in their evolution, and so need a different name. They are called Lepidostrobus

and they were formed from a cluster of modified leaves which produce fertile spore cells. They usually grew at the ends of branches in the canopy.

Lepidostrobus

can exceed 50 cm in length and have a central axis with a helical (spiral) arrangement of the spore-bearing spaces (sporangia). The strobili in Lepidodendron produced two kinds of lycospores: smaller (male) microspores and larger (female) macrospores. These spores united to form the next generation of plants, and, since this required at least a film of water, in some species this happened in the swamp waters below the parent tree.

Macrospores are around 2 mm in diameter, but the microspores are much smaller. They have distinctive trilete sutures ("Y" shaped), on tough waterproof coats to prevent them drying out. They are easily recognised if you have a really good microscope and are often found in fine-grained Carboniferous lake sediments after being blown in by the wind.

Fig. 6: Casts of stigmarian root appendages in Greenmoor Rock

BMBC

Fig. 7: Stigmarian appendages radiating from main axis

Specimen: MuseumsSheffield

Photo: Rick Ramsdale

Root fossils (Stigmaria)

Lepidodendron roots grew up to 15 metres horizontally away from the stem, a feature which would have given stability and anchorage in the saturated soils in which they grew. The root structures are called Stigmaria

and had finer appendages (smaller, hollow root structures) up to 40 cm long and 1 cm across, branching off them in a helical pattern. Also like the leaves, they periodically broke off leaving a circular scar behind on the stigmaria.